Asset Allocation

Over long periods of time, the returns on equities not only surpassed those on all other financial assets, but were far safer and more predictable than bond returns when inflation was taken into account. – Princeton professor Jeremy Siegel from the 2014 preface to his classic book, Stocks for the Long Run

The typical asset allocation recommendation for portfolios of a 60/40 split between Equities and Bonds is as destructive as it is ubiquitous. Warren Buffett dealt with it in this 3 minute segment of a May 6, 2013 CNBC interview: http://video.cnbc.com/gallery/?video=3000166399 The same financial advisors will call for periodic rebalancing, as though that will compensate for 40% of your portfolio being, at best, “dead money.” Indeed, this was even before interest rates dipped into negative territory across much of Europe, meaning you had to pay for the honor of lending your money to the government or even some companies. Some advisors will adjust the percentages based on age, others will add Cash, Commodities and/or Real Estate (REITs) as separate asset classes. Hughes Capital Management takes a much different approach.

Equities

Contrary to what many investors believe, numerous academic studies have shown that, given a sufficient investment horizon, Equities are the safest asset class. In Stocks for the Long Run, Princeton’s Jeremy Siegel points out that in the long run, bonds are riskier than stocks, despite stocks being much more volatile in the short-run. Using a data set from 1802 to 2006, Siegel found that with a 10 year horizon, the maximum loss for a capitalization weighted index of US equities was lower than the maximum loss on corporate bonds or even T-bills. At 20 years, the worst result for the index was a small gain, while both bonds and T-bills worst cases were loses. This conclusion is supported by Ken Fischer’s recent work The Little Book of Market Myths: How to Profit by Avoiding the Investing Mistakes Everyone Else Makes, which found that the long-run volatility of stocks and bonds are very similar yet historical stock returns are nearly double that of their fixed income counterparts.

The results from these two books are confirmed by the Morningstar study “Optimal Portfolios for the Long Run.” Looking at 20 countries each with 113 years of historical returns, the study constructed various portfolios based on risk aversion and time horizon. The paper found very strong evidence that a higher allocation to equities is optimal for investors with longer time horizons, and that equities become less risky over time.

As such, for investors with sufficient time horizons, Hughes Capital Management considers equities to be the bedrock of most portfolios.

Bonds

At their current yields, government bonds, as Jim Grant of Grant’s Weekly Interest Rate Observer has noted, now offer “return-free risk.” As Gary Antonacci, the author of Dual Momentum Investing: An Innovative Strategy for Higher Returns with Lower Risk, has written:

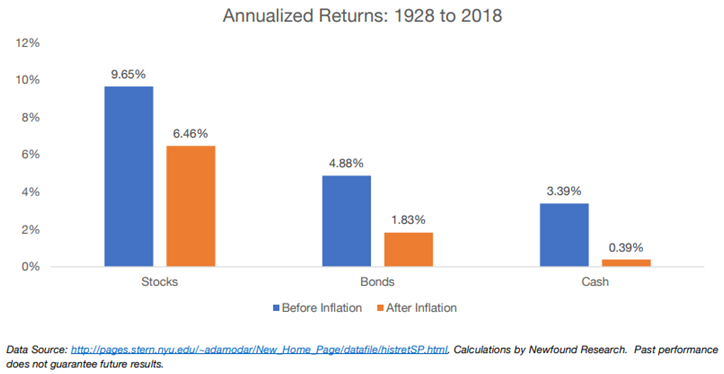

“The average annualized real return after inflation on U.S. long-term government bonds from 1900 through 2013 was just 1.9%, considerably less than the 6.5% average annualized real return from U.S. equities during this same period. Bonds had negative real returns from 1940 all the way through 1981. Purchasers of long-term government bonds in 1941 had to wait until 1991 before breaking even.”

And:

“Given the way that bond prices move inversely to interest rate changes, intermediate-term bonds could lose half their value if their annual yield rises to their long-run average rate of 6.75%. One should keep in mind that real Treasury bond returns were negative for the next 45 years following similar valuation levels as exist today.

Here is what Warren Buffett wrote about fixed-income investing in his 2012 annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway, Inc., shareholders: ‘They are among the most dangerous of assets. Over the past century these instruments have destroyed the purchasing power of investors in many countries, even as these holders continued to receive timely payments of interest and principal… Right now, bonds should come with a warning label.’”

While there may come a time in the future when long-term Bonds once again make sense as a part of a diversified portfolio, currently it is an asset class best avoided.

Cash

Equities have historically returned 10% a year. Move the decimal point 2 places to the left and you have what cash is currently yielding. That is an opportunity cost of 9.9% annually. While holding cash may be necessary at times, cash is “dead money” and hinders capital appreciation

Real Estate

Real Estate exposure can be a critical component of a well-diversified portfolio. As the Forbes Real Estate Investor has stated: “Commercial real estate is the third largest asset class in the U.S., representing some $6.5 trillion of market value, or roughly 12.4% of the $52.8 trillion investable universe in the U.S.” The best way to obtain exposure to this market is through REITs, which over the past two decades have outperformed the broader equity market.

While the short-term volatility of REITs can be jarring (as the Great Recession in 2008 demonstrated), with a long time horizon their risk profile dramatically improves. The Morningstar graph below illustrates the realized gains and losses in REITs for one-, five-, and 15-year periods. Of the 42 one-year periods from 1972 to 2013, only eight resulted in a loss. By increasing the holding period to five years, only one of the 38 overlapping five-year periods resulted in a loss, while none of the 28 overlapping 15-year periods from 1972 to 2013 resulted in losses.

Commodities

Many investment advisors recommend a significant allocation to commodities for returns uncorrelated with the rest of the market. And while the returns from the asset class are indeed uncorrelated, for the past few decades the roll yield on many commodity futures contracts have been negative, meaning investing in these contracts has been a losing game.

In a 9/1/16 interview titled “Why Investing in Commodities Can Be Challenging”, Morningstar’s Bri